There are some things in life that stop you dead in your tracks, grab you by the balls and make you feel utterly disappointed in the world. Things that should not happen. Jimmy Saville for example, should not have happened. Selling Britain’s beloved chocolate company Cadbury’s to a bloody American cheese company should just not have happened (this upset me a great deal as while I’m not particularly nationalistic I adore chocolate and that Brummy choc recipe should not have been passed onto the land of Reece’s and other terrible chocolate disasters.) Plus, it was one of the few things that made me proud to be British: “Yes, we invaded Iraq, yes we’re the arrogant ones in the EU and yes, I’m terribly sorry about the colonial stuff – but have you tried a Wispa? They’re really very good.”

Anyway going back to the things that should not happen. Seas should not shrink. And they should definitely not shrink so fast that they could disappear over just 70 years, killing millions of fish and wildlife, throwing thousands of people into poverty and completely screwing up the climate.

But that is exactly what is happening to the South Aral Sea in Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan. Once a significant blue mass on the world map, today you will find nothing more than a few small little blobs around the Uzbek and Kazak border. And even that is probably out of date and not really representative of what is left there today.

This map shows the size of the sea as it was in the 1950s on the far left, shrinking over the years until you can see the small scrap of blue on the right, which is how it stood in 2009. It is even smaller today.

In the 1950s the sea was the second largest salt lake in the world (after the Caspian Sea) but that all changed after the Soviet Union had the GENIUS (please note sarcasm here) plan to divert the Amu-Darya river, which once filled the sea, across the deserts of Turkmenistan to enable cotton farming instead. This man-made channel of water, called the Karakum-Darya, took a whopping 70 percent of the river’s water that would have otherwise been flowing into the sea. It has quite literally sucked it dry.

While Turkmenistan enjoyed the benefits of its new water supply, the Aral Sea started shrinking rapidly and split in two (now known as the South Aral Sea and the North Aral Sea).

Today the water volume is just a tenth of what it was 60 years ago and its shores have moved a huge 170km. Boats were beached as the water withdrew and it also left behind ghost towns and villages that had once prospered on fishing and sea life and were now left with nothing.

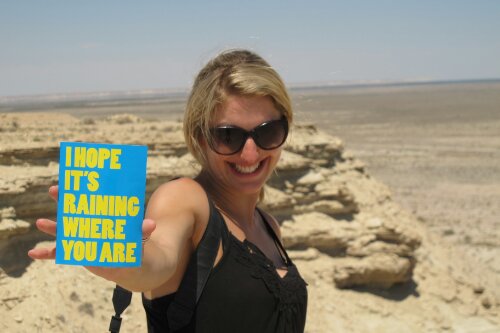

Visiting what remains of the South Aral Sea, as bleak as it may sound, was high on our list of things to do in Uzbekistan. Our guidebook, which was published almost three years ago, warned that the sea might not outlast the life of the book. So we tentatively made some enquiries.

But yes, we were told the sea is still there. Shallower than ever and even further away, but yes, still there.

The four of us piled into a khaki green Russian jeep (Matty, the Mongoose and I have been joined by the Mongoose’s lovely girlfriend Karen who has both given me the girly companionship I have been craving, and is supporting my campaign for ’emergency water and biscuit’ supplies on all excursions).

The jeep, while appearing to chunter and chug its way across the urban streets of Uzbekistan uncertainly (while stinking of petrol), came into its own as we entered the dusty, dry desert terrain.

We spent hours hurtling up and down the dried, bumpy mud tracks with our lovely Russian driver Costa, who took no fear in pushing the jeep to its limits. As we sped across the uneven ground, birds and wildlife that had nested in the grassy ridge between the tracks suddenly took flight, sometimes too late and bouncing right off our windscreen.

Often the ridge in the middle of the tracks became so high I felt sure it would damage the underbelly of the jeep or that one wrong nudge on the steering wheel would send us skidding over it and tumbling across the desert.

I tried to ignore these thoughts as Costa cried: “Scream if you want to go faster”, in Russian. Well, we’re not really sure if that was what he was saying but evidence would suggest those were his exact words. So as I squealed and screamed and covered my eyes for what felt like hours on end, after passing only one other vehicle on the tracks, we finally reached our first stop. Sudochje lake.

Once very close to the Aral Sea, ships would come to the freshwater lake for drinking water. Today it is surrounded by dry, barren land and we still had another few hours of desert driving until we were to see what remains of the sea.

We continued the long, hot drive. The Mongoose’s watch, which likes to predict storms on fine sunny mornings and demands constant collaboration with every metre we climb up mountains, claimed it was 41 degrees in the shade of the car. For once I was inclined to believe it.

As we drove we watched pockets of wind whip up dry dust in its path creating mini tornadoes that skidded across the plains, with their skinny tails reaching right up to the clouds.

But then finally to our right, a sparkling blue water came onto the horizon. “The Aral Sea?!” We cried to Costa (something we had done at the lake and every time the landscape changed). He nodded and smiled, “Aral Sea,” he confirmed.

It was glistening and beautiful, and just what our sun-baked dusty bodies were crying out for. As we got closer the scenery changed into a dramatic, dinasour-like land full of rocks and hills, and we found ourselves perched at the top of what would have once been the seashore, not all that long ago. But today it is a plateau with a sheer drop down some 30 metres or so onto the former seabed.

We drove down a track that took us down the plateau before continuing a good mile or so along the dried up sea bed until we reached the shimmering water ahead.

Desperate to get in the cool, refreshing water, we each shamelessly semi-hid behind a jeep door to change into our swimwear and ran towards the waves. It was just like something out of Baywatch. Ahem.

Ok, it didn’t really go like that. The sea is now 10 times saltier than it was 60 years ago when it began to shrink and as a result the ground leading into the sea has a cracked, hard, salty layer on top so we sort of awkwardly hopped and stumbled into the sea.

Then almost as soon as our feet made contact with the sea, the soil turned into a deep, squelching, thick mud that made it almost impossible to walk. The water should have been around our ankles but instead we were knee deep in sinking mud. My strategy was to hold everybody’s hands around me and pull them down too. Matty’s tactic was to take up an odd, quick little run that saw him lift each foot in front of the other as quickly as he could before he could submerge into the seabed. Both kind of worked.

Some serious comedy walking later and we were freed by the mud and released into the Aral’s waves. Our bodies floated in all positions, buoyant from the salt and we slowly drifted across the warm water before smearing each other in the seabed mud, which is meant to be even better for the skin than that of the Dead Sea in Israel. It was the sea dip I had been dreaming of on this landlocked adventure of ours. Sheer bliss.

A swift water-bottle-shower later we returned to the top of the plateau to set up camp and watch the sun say its goodbyes for the day.

As the sun lowered a white haze spread over the sea and across its old, dried seabed.

“It is the salt,” said another guide, who had joined us with a second jeep of travellers.

“It never used to do that,” he added, already his back turned as he walked away from the man-made mess before our eyes.

That’s how everybody here talks. It never used to be like this, they say wistfully when you ask them questions.

And as I stared out to get one last look at the thrashing waves of the sea below the haze, I felt overwhelmed with a sense of helplessness, as if I had been told someone out there was drowning but nobody could reach them.

It should never have been allowed to happen, but it did. And the next time you read about the South Aral Sea it will probably be in a history book.

Travel tips

How to visit the Aral Sea?

You will need to hire a 4×4 and driver who knows the desert well – there are dozens of tracks all over the place and I imagine it would be very easy to get lost.

There are a number of companies that run the trip from Moynaq and Nukus. We used a company called Bes Qala Nukus (phone: 2245169 email: bqntravel2006@rambler.ru) which cost $400 for the jeep hire, plus $35 each for food for two days and camping equipment. As there were four of us it cost $135 each for two days.

Our driver, although he did not speak English, was absolutely wonderful. He constantly went the extra mile and was very sweet (he ran into the Aral Sea jumping the waves as if it was the first time not the umpteenth time he’d done it). The company also had an English speaking driver who was doing a tour over the same days and in the evening he took great effort to explain everything to us and answered all our questions. The food was very nice and we could not have asked for more.