So here’s the slightly embarrassing thing about our recent jaunt across the Silk Road from Turkey to China: We made for terrible traders.

Following the ancient trade route from the west to the Far East, we felt obliged to get involved with a little trading of our own.

So when we were in Turkey, the first post of the Silk Road on the west, we thought long and hard about what we could trade for some silk in the Far East.

What had traders never before carried across 7,000 miles of treacherous desert, remote mountain ranges and right across the Caspian Sea? What would be gazed at in awe as soon as we reached China and have our fellow merchants fawning over us to give their finest silk in exchange?

And then suddenly we saw it. The shiny, almost marble like onyx egg.

We were in Cappadocia at the time, admiring fairy chimneys and what-not, when we spied a man spinning onyx stone into egg shapes.

Yes, we thought, that will secure our fortune and reputation as great traders. So we purchased one at the bargain price of £5.

We lovingly wrapped it in the plastic bag that it came in and tucked it safely away in a corner of Matty’s day bag. The egg would make us rich, we vowed.

We carried it through Turkey and pulled funny faces with it.

In Georgia we took it all the way to the Gergeti Glacier.

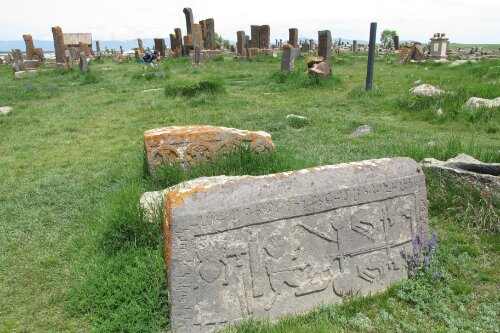

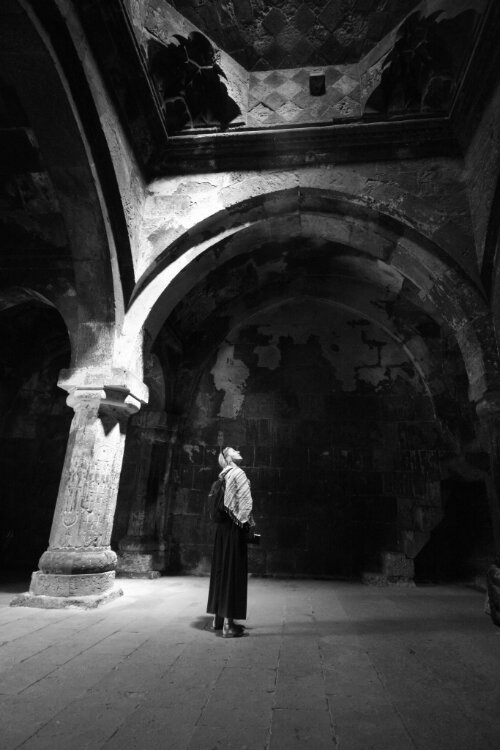

In Amenia we showed it a large lake by a beautiful church.

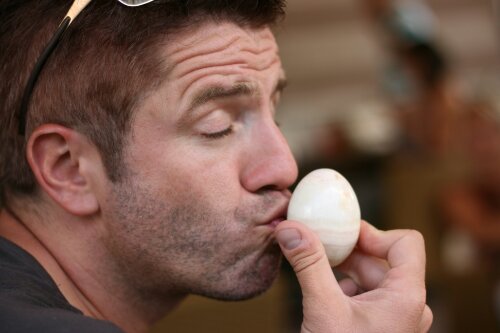

In Azerbaijan Matty got a bit inappropriate with it.

In Turkmenistan we took it to the ancient ruins of Merv.

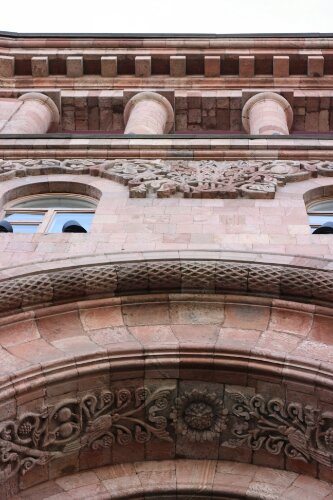

In Uzbekistan the egg saw the beautiful blue tiled mosques of Samarkand.

In Tajikistan the egg got all giddy at high altitude.

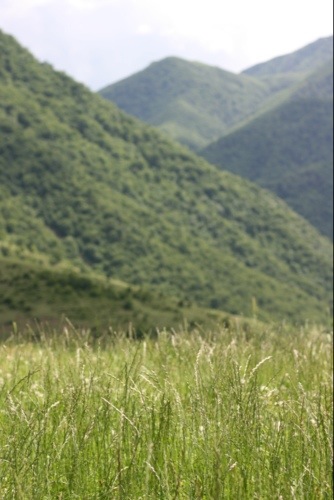

In Krygyzstan the egg got all arty among the rolling hills.

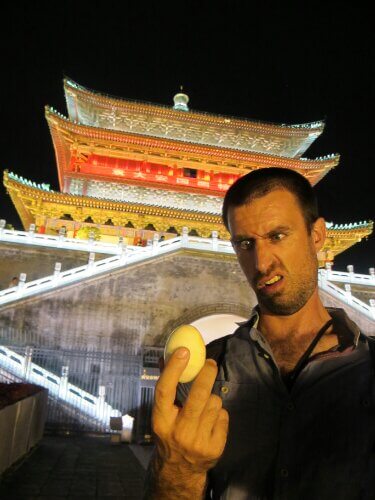

And then it got all the way to China… and enjoyed posing by the Bell Tower in Xi’an, our final stop on the Silk Road.

And it had its last moments with the Face of Ignorance…

And then finally the big day arrived. Four and a half months after making that fateful purchase Cappadocia, it was time to trade the egg at the far eastern post of the Silk Road; Xi’an, China.

Our first mistake was that we had grown unnaturally attached to the egg. It sort of felt like the fourth member of the clan, so to speak. It had seen everything we had… If eggs could talk. I fear this may have affected our professionalism.

Our second mistake was the egg was no longer in top notch condition. Truth be told the plastic bag didn’t quite provide the protection we had initially hoped for and as Matty threw his bag down after a few local special brews, we would hear it smash against the hard floor and cringe, hoping for the best.

Our third mistake, and I think this was where we really went wrong, was that someone had already taken onyx eggs to China. To our dismay we found rows and rows of egg shaped onyx creations, even onyx egg holders and other strange, elaborate statues that we fear somewhat undermined the status of our own little onyx treasure.

And finally, we couldn’t find the silk market in Xi’an so we headed to the Muslim quarter and hoped for the best.

After spending a couple of hours being distracted by the great street food and souvenirs that line the lantern adorned lanes of the Muslim Quarter we remembered our mission and hunted for a silk trader.

Eventually, by a stroke of luck as we made our way to the train station almost completely defeated, we chanced upon a lady selling silk scarves.

We played by all the old ancient trading rules – causally running the scarves trough our fingers, pretending we were only half interested. Well, until I cried: “This one, this one,” pointing enthusiastically at a piece of white silk with Chinese writing on it. That might have been another mistake.

So, the haggling started. She started the bidding at 100 Yuan (about £10), to which I came back with an offer we thought she couldn’t turn down: The Egg.

“This egg has travelled 7,000 miles from Turkey – it’s original onyx from Cappadocia,” I explained.

“We saw it being made by hand,” added the Mongoose.

We all looked towards her expectantly. And then something happened that I never, ever foresaw.

She laughed. She looked at our little old egg and broke into a great, mighty cackle.

“Ok, 10 Yuan and the egg,” I offered quietly.

More laughter. The bidding continued but she seemed to be more preoccupied with the money than the egg. It was not going to plan.

After a little while she softened and took the egg into her hand. She smiled.

“50 Yuan and the egg,” she offered.

Ok we agreed. We had a train to catch after all.

We took the silk scarf into our hands, which we plan to cut into three pieces because what better souvenir could three traders ‘cut from the same cloth’ possibly hope for?

As the exchange was made we watched in surprise as she placed the egg into her handbag instead of on the market stall.

“I think it will bring me luck,” she said smiling, still giggling a bit.

And we nodded in agreement. Financially it may not have been our best move – travelling the egg across the Silk Road cost us about £5,000 each, plus the £10 spent on the two transactions. We were left somewhat in negative equity.

But luck? Yes, the egg had definitely brought us lots of that.