It was the day after I fell over while climbing down a 2,300 metre peak, landing on my knees in such a way that took my breath away, and the morning before I fell into a river while trying to jump between large rocks in the water. Really, it is a wonder that my feet keep me upright at all.

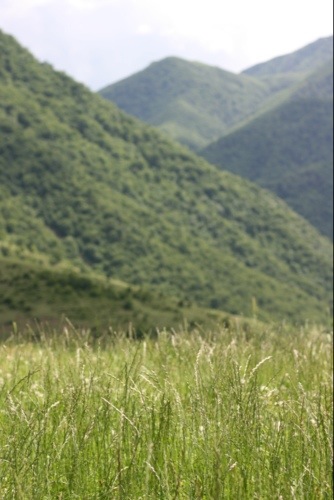

But anyhow, it was on this morning between calamities, after eating a breakfast of mammoth proportions, that I found myself at an Uzbek wedding in the village of Langar, near Shakribsabz. We had spent the previous night with a family in the mountainous region and that morning our host announced that we would call in at a local wedding before a short trek through the canyon that connects Langar with the next village.

I looked dubiously down at my formerly black, now mud stained, Northface trousers. As mentioned, I had not fallen particularly gracefully and the impact had not been kind on either my knees – or my trousers, which now sported a childlike hole in the right knee.

“Oh,” I said. “Do you have a needle and thread?”

Ten minutes later, with the trousers suitably sponge cleaned and darned, I put on my hiking boots and looked at my greasy, suntan-creamed face in the mirror. I was ready for the wedding.

We jumped into a cramped minibus, where we sat on top of a few other wedding guests, and overtook a few donkeys before pulling over on the side of the road. From there we followed the sound of loud music over a little stream and up to a house where the wedding party was in full swing.

As we walked up the small driveway to the house, which had dozens of tables and chairs set outside, a man with an oversized camcorder filmed our dishevelled entrance. We were warmly greeted and shown to a table, which was lined with food and vodka within minutes. It was 10am.

The Uzbeks are some of the friendliest people I’ve met on this trip. When they say hello (Salam), they do so holding one hand to their heart, nodding earnestly and flashing entire gums full of gold teeth as they do so. Their hospitality knows no bounds and this wedding was no exception.

Tumbler glasses were soon filled with vodka and huge dishes of Plov, their national dish of fried rice and carrots, with slow cooked, tender chunks of beef or lamb, were placed in front of us. We toasted, we drank, we grimaced. Repeat. Repeat. Repeat.

We politely but enthusiastically nibbled away at the juicy, fried dish in front of us, hoping our big grins made up for the small mouthfuls, and wishing we had not all gone for a second egg at breakfast.

Then, as we were tucking into our fourth vodka of the morning, Matty’s smile froze. We heard the words “Anglia” and “Germanie” bellowed out over the PA system that seemed intent on keeping the whole village up to date with the latest party developments.

“They are talking about us,” he whispered.

And sure enough the MC of the party, clutching his microphone and prompt cards, made his way over to our table where he talked in an increasingly excited and frenzied manner, giving a grand introduction that would have even done justice to the final Beatles concert.

And then somebody pulled me up, and to the sound of clapping and cheering, the microphone was put in my hand.

“Salam my friends,” I started. Or something like that. More cheers and laughter. I cleared my throat and went on to say my piece, thanking our hosts for the food and hospitality. Or at least I think that’s what I said. Truth be told, it was all a bit of a blur as I tried to ignore the delayed echo on the microphone as my words carried across the village.

Next up was Matty, he sent his best wishes to the young couple and wished them a life happiness. Darn, I thought, I’d forgotten about them.

And then it was over to Chris, our third travelling companion for these few days, who offered them some words of wisdom in German and was also received with great applause. Sadly the Mongoose was not there to offer them his Irish sentiments as he has nipped over to Afghanistan for a few days. We on the other hand have been denied visas so it was our fate to now take to the dance floor.

Matty tried to refuse initially, a tactic he so easily gets away with at English weddings, but the Uzbeks are as persuasive as they are hospitable and he found he was the first to be dragged to the dance floor. Then one of the women made eye contact with me and I found myself up besides him.

The Turkish and Middle Eastern sounding music bellowed out once more, as deafening as in an Uzbkek taxi, and we found ourselves moving our arms and bodies in unusual ways as we attempted to copy those around us.

Notes of 1,000 Uzbek Sommes were thrust into my hands and into the headscarves of other women around me, which Matty has since likened to a really bad strip dance, but left me thoroughly confused while I danced like an unco-ordinated extra in Arabian Nights. And then a baby was thrust into my arms and I really wasn’t sure what to do with that.

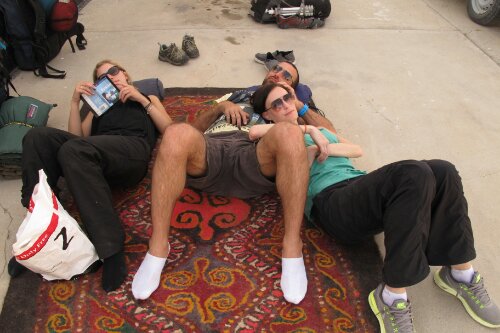

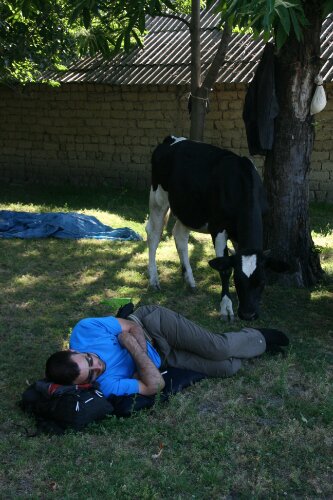

No fewer than four or five songs later we were allowed to excuse our sweaty selves and retired to a shady spot under some trees with the old men, who had been wise enough to retain their positions throughout the dancing.

More vodka was thrust upon us. But despite all the food, merriment, booze and dancing I had that nagging feeling that something was amiss.

“The bride and groom,” I suddenly cried. “Where is the bride?”

Inside, I was told. The bride has to stay inside the house today.

“But she’s missing her own party,” I exclaimed somewhat incredulously. Yes, yes, our guide agreed, but she is with all the unmarried girls in the house.

I asked if I could see her and was permitted to do so.

I was led inside a cool, dark room at the far end of the house and as my eyes adjusted to the light, I spied a small girl get up from the back of the room. I went over to her and earnestly congratulated her in English with a few Uzbek ‘thank-yous’ thrown in. She must have been no older than 17 and incredibly sweet.

She is, of course, the one on the left.

The wedding was actually yesterday, I was told. This was the party for the village and she would not get her ring until the end of Ramadan, which begins in about a week. I couldn’t help but hope she would get more out of the marriage than the wedding party, which sounded like it was still in full swing outside.

As we were seemingly the only guests with a camera, she posed for pictures with her family, which I have promised to send on. And then I was spat back out into the party, where Matty and Chris were holding court with the vodka.

And it was only then that we set off on our canyon trek. And that is why I fell in the river.